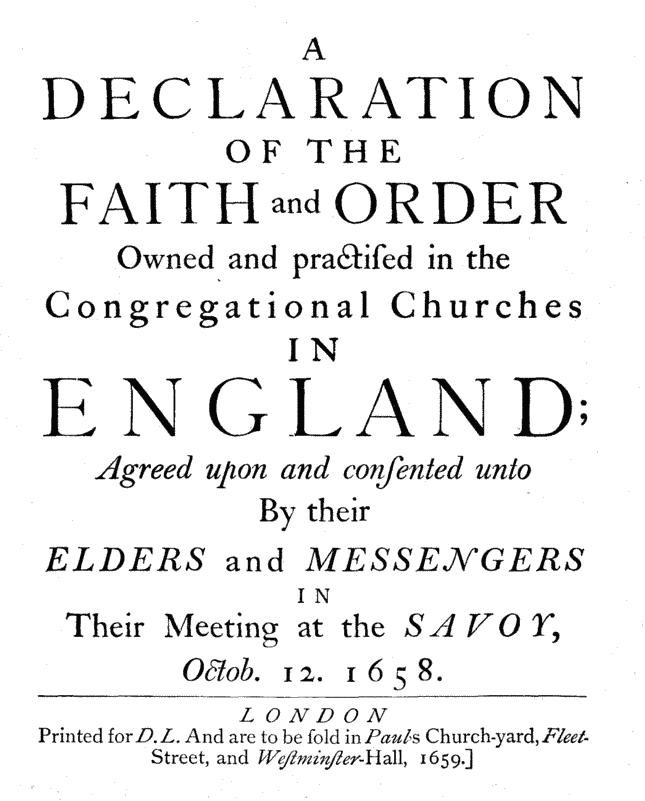

On October 12, 1658, English Congregationalists made a significant theological and ecclesiastical move by adopting the Savoy Declaration of Faith and Order, a confession that helped define their identity during a turbulent time in English religious history. This moment was not just about doctrinal clarity—it was a bold assertion of independence, unity, and commitment to the authority of Scripture.

The Savoy Declaration was adopted at the Savoy Palace in London, where a synod of Congregationalist leaders gathered in the wake of the English Civil War and amid the shifting religious landscape of the Commonwealth period. Many of these ministers had been influenced by the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), the Reformed doctrinal standard crafted primarily by Presbyterians. However, the Congregationalists sought a confession that better reflected their ecclesiology—especially their belief in the autonomy of the local church.

Thus, while the Savoy Declaration closely mirrors the Westminster Confession in its theological content—affirming doctrines like the Trinity, justification by faith, and the sovereignty of God—it diverges notably in church polity. The Congregationalists emphasized that each local church was self-governing under the rule of Christ, free from outside ecclesiastical control. This contrasted with the Presbyterian model of church governance through regional assemblies and synods.

The Declaration also provided guidelines for church discipline, membership, and the proper administration of sacraments, all from a distinctly Congregational perspective. Yet, the authors, including prominent theologians like John Owen and Thomas Goodwin, were careful to promote unity among believers. They stated a desire not to “divide the godly party,” but rather to provide a shared foundation for those who held to Reformed doctrine while practicing Congregational polity.

The adoption of the Savoy Declaration marked a defining moment for English Congregationalism. It helped solidify the theological and practical identity of Congregational churches, offering a middle path between Presbyterianism and more radical separatist movements. It also reinforced their commitment to religious liberty, the supremacy of Scripture, and Christ’s headship over the church.

Though political shifts following the Restoration would push many Congregationalists into nonconformity, the Savoy Declaration remained a lasting symbol of their convictions. Today, it stands as a historical witness to the careful balance they sought between doctrinal orthodoxy, ecclesiastical independence, and Christian unity.

Also On This Day

1951 – Simon Kimbangu, the founder of the Kimbanguist church, died in prison.